Jump to:

News | Fundraising | Friends | About | Life | Writing | Politics | Legacy

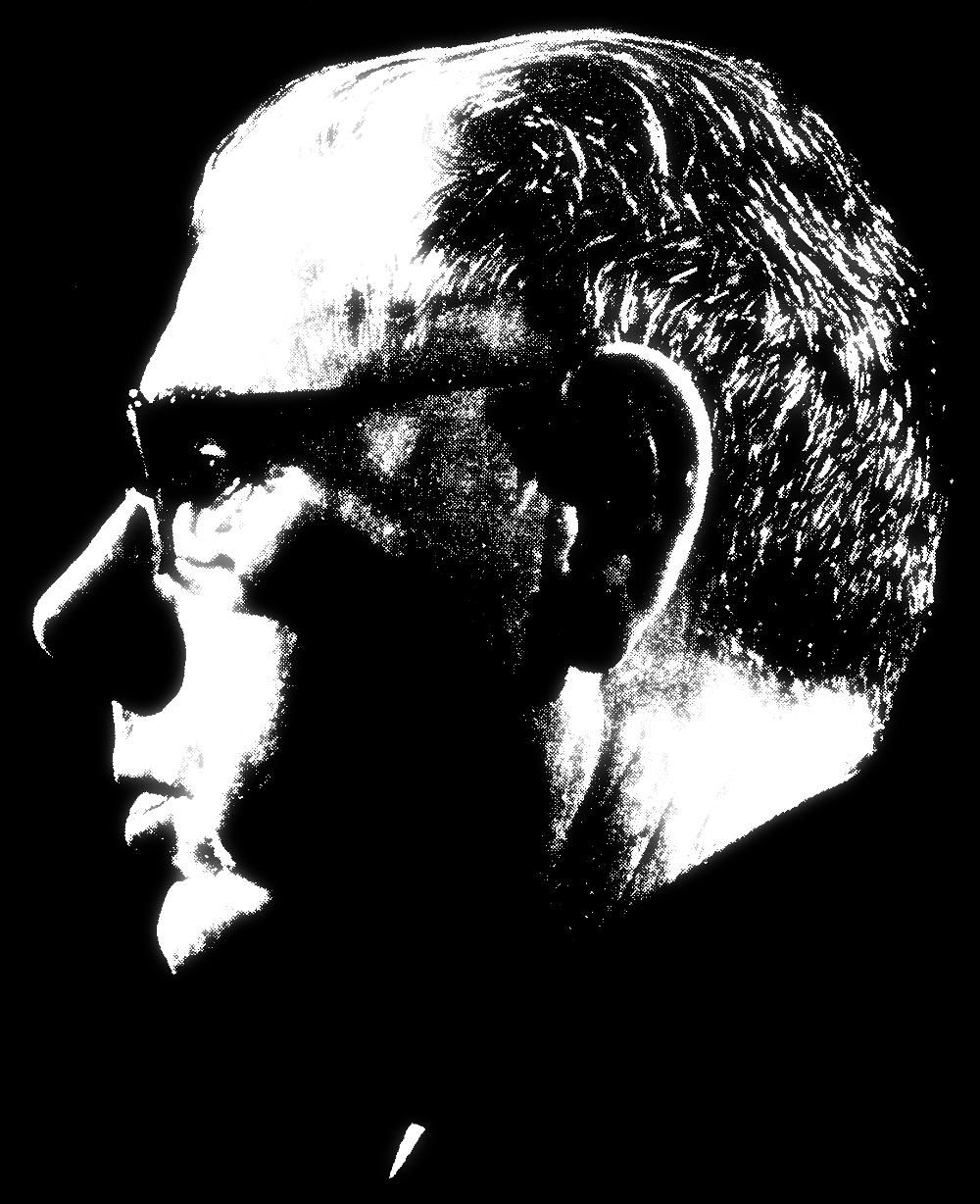

This page provides an overview in English of the content of our website, which consists of information and other material about the prominent Irish-language prose writer, language activist, and social and political activist, Máirtín Ó Cadhain (1906–1970).

An index of this site’s English language content can be found in the legacy section.

If you are not fluent in Irish and would like to find out more about any of the following topics, please feel free to get in touch. Contact details can be found at the foot of this page.

Latest news

Ó Cadhain statue unveiled

23rd July 2022; 3.00 p.m.

An tAirdín Buí, An Spidéal , County Galway.

Máirtín Ó Cadhain commemorated on his native soil.

A life-size bronze statue of the major Irish-language writer and language activist, Máirtín Ó Cadhain, has been executed by the noted sculptor, Alan Ryan Hall. Funding and support for the project were provided by Gaeltacht and academic organisations, relatives of Ó Cadhain, and by individual members of the public.

The statue was erected at An tAirdín Buí, just east of the village of An Spidéal and across the road from the Texaco garage. Galway County Council granted planning permission for the erection of the statue at this spot to Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain in 2021.

The statue was officially unveiled by Dónall Ó Braonáin, Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge, on Saturday July 23rd at 3 pm.

Fundraising

Fundraising page 🔗Friends of Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain

8th July 2022: The list of friends — Cairde Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain — was updated.

The following lists include those who agreed to have their names acknowledged publicly.

Other people/organisations donated subscriptions on a private basis and we heartily thank them also. A few others made donations without leaving their names, and we are equally grateful to them also. You are all our friends!

Bosom Friends

People or organisations who donated at least €5,000.

- Údarás na Gaeltachta

- Na Forbacha, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Cumann Forbartha Chois Fharraige

- Indreabhán, Co. na Gaillimhe.

Great Friends

People or organisations who donated at least €1,000.

- Bríd Cooley

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Tarlach ⁊ Áine de Blácam

- Inis Meáin, Árainn.

- Bernadette Ní Chadhain ⁊ Ailín Bregazzi

- Clontarf, Dublin 3.

- Colm Ó Cadhain

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Seán Ó Cadhain

- Raheny, Dublin 5.

- Siobhán Uí Chadhain

- Raheny, Dublin 5.

- Brian Ó Cléirigh

- Wexford, Co. Wexford.

- Ruairí Ó hUiginn

- Blackrock, Co. Dublin.

Loyal Friends

People or organisations who donated at least €500.

- Cáit Ní Chadhain

- Bóthar na hUaimhe, Baile Átha Claith 7.

- Fidelma Ní Ghallchobhair

- Ranelagh, Dublin 6.

- Míċeál Ó Loċlainn ⁊ Máire Ní Neachtain

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- UCD

- UCD School of Irish, Celtic Studies and Folklore, Belfield, Dublin 4.

- Máire Uí Laoi

- Indreabhán, Co. na Gaillimhe.

Cairde Gael

People or organisations who donated at least €100.

- Aisteoirí Bulfin

- Dublin.

- Máire ⁊ Pádraic Breathnach

- Indreabhán, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Micheál Briody

- Helsinki, Finland.

- Pádraic de Bhaldraithe

- Leitir Mealláin, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Ann Burnell ⁊ Brian Spring

- National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Co. Kildare.

- Aodhán ⁊ Bridie Mac Cormaic

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Anne Mc Quillan

- Drumcondra, Dublin 9.

- Muintir Mhic Dhonncha agus Uí Dhubhda

- Ráth Cairn, Co. na Mí.

- Eilís Ní Anluain

- UCD, Dublin.

- Paula Ní Shlatara

- Ranelagh, Dublin 6.

- Professor Meidhbhín Ní Úrdail

- Ballinteer, Dublin 16.

- Seán Ó hAodha

- Indreabhán, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Seán Ó Cionfhaola

- Castlebarr, Co. Mayo.

- Éamonn Ó Cíosáin

- Lucan, Co. Dublin.

- Máirtín Ó Cléirigh

- Dublin.

- Mac Dara Ó Curraidhín

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Cormac Ó Gráda

- Dublin.

- An tOllamh Cathal Ó Háinle

- Portmarnock, Co. Dublin.

- Éamonn Ó hÓgáin

- Clondalkin, Dublin 22.

- Bríd Ní Chadhain

- Templeogue, Dublin.

- Caitríona Ní Chadhain

- Donnycarney, Dublin.

- Máire Ní Chadhain

- Marino, Dublin.

- Seosaimhín Ní Chadhain

- Marino, Dublin.

- Síle Ní Mhurchú

- The Lough, Cork.

- Ciarán Ó Duilearga

- Brussles, Belgium.

- Éabha Rosenstock

- Glenageary, Co. Dublin.

- Dearbhaill Standún ⁊ Charlie Troy

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Donal Standún

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Lisa Uí Choistealbha

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Treasa Uí Lorcáin

- Ros an Mhíl, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Neilí Uí Neachtain

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

Other Friends

People or organisations who donated up to €100.

- Róisín Adams

- Indreabhán, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Colm Connor

- Wexford, Co. Wexford.

- Beairtle Ó Conaire

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Páid Ó Donnchú

- Na Forbacha, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Tomás Ó hÍde

- An Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe.

- Anonymous friend

- ??? ??? ??? …

Our website

This website provides both biographical material and information about Ó Cadhain’s political activity, as well as accounts of his literary works, including academic articles and reviews penned by various experts in the field of Irish-language literature and criticism.

The site includes a number of audio and video clips of talks and interviews with or about the writer and his work. These are taken from various radio and television programmes, from films and from spoken-word audio albums. Further material is being added on an ongoing basis.

The material on this website was compiled by Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain, who also prepared the biographical and explanatory text.

Iontaobhas Uí Cadhain

Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain began working in 1988 as a committee to examine Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s papers and to make decisions about how best to deal with them. Having fully catalogued them, the papers were then presented to Trinity College library on 10 June 1996, where they can be consulted. The Iontaobhas had the papers assessed and, with advice from esteemed academics, most of the material was published between 1995 and 2002.

The Iontaobhas officially became a Company Limited by Guarantee not having a Share Capital on 10th July 2015, and was granted charitable status by the Charities Regulator on 10th August 2018.

Most of the work that was unpublished at the time of Máirtín’s death in 1970 has now been made available. And more importantly, Ó Cadhain’s complete works are now in print for the first time in decades, thanks in the main to the publisher, Cló Iar-Chonnacht.

His work is now becoming accessible to those who are not fluent Irish speakers. Two different English translations of Cré na Cille were commissioned, one by Alan Titley, The Dirty Dust, published in 2015 and the other by Liam Mac Con Iomaire and Tim Robinson, Graveyard Clay, published in 2016 (both by Cló Iar-Chonnacht and Yale University Press). Translations to a range of other languages have also been published including Norwegian, Danish, German, Nederlands (Dutch), Turkish, Hungarian, Czech and Italian, and others are said to be in preparation. Some of his most famous short stories have also been translated to other languages in recent years, with more in development. New interest is undoubtedly being expressed in Ó Cadhain’s writings.

Iontaobhas Board members

- Cathaoirleach (Chairman):

new appointment to be announced. - Leas-chathaoirleach (Vice-chairman):

new appointment to be announced. - Rúnaí (Secretary): Máirtín Ó Cadhain.

- Stiúrthóir (Director): Seán Ó Cadhain.

- Stiúrthóir (Director): Fidelma Ní Ghallchobhair.

Current, medium- and long-term plans

- This website is very much an ongoing project. Further material, much of it multimedia, is being sourced from relevant authors and organisations. This is being added as clearances are granted.

- Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain is actively engaged in a project to comission a life-sized bronze statue of Máirtín Ó Cadhain. The intention is that this statue be located in An Spidéal village itself (Spiddal, in English) or possibly on an appropriate site in the surrounding area. Research and preparatory work have already been carried out and planning permission is being sought.

- It’s planned to develop a permanent exhibition relating to Ó Cadhain; again, to be located in or around An Spidéal village.

- The Iontaobhas has long-term plans to actively encourage and support new conferences and seminars that focus on Ó Cadhain’s work and legacy.

- Rather more ambitiously, we’re preparing plans:

- To buy the house in which Máirtín Ó Cadhain was born and to develop it as a place of interest. The house itself has fallen into considerable decay over the years and the land around it is extremely overgrown. The immediate plan is to stabilise as much of the remaining building as possible and to bring the site into a condition suitable to facilitate visitors. Proposed facilities for the initial stage of development include pedestrian access pathways, a car park and a series of weatherproof informational plaques about Ó Cadhain, to be erected in a non-destructive manner throughout the site.

Ó Cadhain’s life

Máirtín Ó Cadhain was born on 20 January 1906 in An Cnocán Glas, a townland about half a mile or one kilometer west of the village of An Spidéal, County Galway. (Regardless of the appearence of other dates in various items of official documentation, Máirtín’s family is in absolutely no doubt that this is the correct one.) He was the eldest to survive of thirteen children born to Seán Ó Cadhain and his wife, Bríd Óg Nic Conaola, small farmers who farmed half a holding beside Seán’s brother, Máirtín Beag, who farmed the other half-holding. The Ó Cadhain family moved down from the Oughterard area in 1839, having bought this holding from Lord Kilannin. Seán, Bríd and Máirtín Beag were all noted shanachies, (storytellers; from the Irish seanchaithe), and the young family members were exposed to a rich tradition of Irish folktales, songs and historical lore.

Máirtín attended primary school in Spiddal from 1911 until 1924, having spent the last six years or so as a monitor there. He won the King’s Scholarship which allowed him to attend Saint Patrick’s College, Drumcondra in Dublin where he trained as a primary teacher, 1924–26. While teaching in Galway he attended a night-course for primary teachers in the university there and attained a diploma in education in 1927. Thus ended his formal education but he continued to be an avid learner throughout his life through reading voraciously, through learning from others and through travelling widely. He became multilingual, acquiring over time the Celtic languages, French, Spanish, Italian, German and Russian.

He took up a permanent teaching post as principal of the primary school in Camus, an Irish-speaking area in Conamara, in 1927 where he taught until 1932, moving then to the school in Carnmore, about 13 kilometers east of Galway. In 1936 he was dismissed from his post by order of the local bishop due to his political activities. He had become a member of Óglaigh na hÉireann (the Irish Volunteers) while still in Camus and continued to be active as a captain while in Carnmore. Thus he sharpened his skills as a political organiser and strategist. He founded a branch of Conradh na Gaeilge (The Gaelic League) there — Carnmore was a breac-Ghaeltacht; an area where some residents speak Irish and others English). He was now an overt language activist, although he had been penning material in Irish since at least 1928, starting with folklore collections, reviews and translations. Máirtín was held in extremely high regard as a teacher by the communities in Camus and Carnmore, but his career as a primary teacher ended in December 1936. He would have other students to teach, however, starting with student teachers on summer Irish-language courses in An Cheathrú Rua (Carrowroe), Conamara, where he met his future wife, Máirín Ní Rodaigh in 1932.

Having moved to Dublin in late 1936, he taught Irish to adults in Conradh na Gaeilge. In 1939, he met John Ellis Caerwyn Williams from Wales who taught him Welsh and to whom he in turn taught Irish. He was an active recruiting officer for the Irish Volunteers during 1937–8 and in 1939 he was captured and interned in Arbour Hill prison from September until December, during which time he taught Irish and other languages to other internees. He was again interned from 1940–44 in the Curragh Camp, County Kildare, where he taught Irish, History and French. There he improved his French and started learning Russian. He read works by the major French and Russian dramatists and storytellers, as well as the works of important European philosophers and theologians. He then gave a series of lectures on philosophy and sociology to his fellow internees. Both of his parents died while Máirtín was interned in the Curragh. He was allowed out on special leave to attend the first of these funerals but not the second.

On his release and return to Dublin in 1944, Máirtín found it very difficult to find gainful employment. However, as a result of campaigning and canvassing by some influential friends, he was provisionally admitted to a post in the civil service in 1947 as a translator of legislation, where he remained until 1956. As with all his previous placements, he didn’t waste any time in this job. Whenever translation work was at a low ebb, he amused himself by reading books about Old Irish and the old Irish legal system.

Having a secure income, Ó Cadhain was now in a position to marry Máirín Ní Rodaigh, who was a primary teacher from County Cavan. In 1952, Máirín began to teach in the newly-founded gaelscoil, Scoil Lorcáin in Blackrock in south County Dublin. The Ó Cadhains often hosted family and friends from Conamara and elsewhere visiting Dublin. They had no children. Máirín died in 1965 and five months later, Máirtín’s younger brother, Seosamh (Joe) who had lived on the north side of Dublin, also died, leaving his widow and nine children in his wake. Máirtín offered to take two of the nine to live with him as a support to the young widow, Cáit Uí Chadhain. Thus, the then teenagers, Bríd and Mairéad Ní Chadhain, went to live with him and Mairéad was still living there when Máirtín himself died in 1970. Máirtín had employed a maid from Conamara who took care of the cooking and housework.

While Máirtín worked as a government translator, his friend and publisher, Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh, established a small committee with the aim of finding a university post for the by now blossoming writer. This was no mean task, given Máirtín’s political activism as well as the fact that he had no university qualifications. However, to its great credit, Trinity College, Dublin agreed to the committee’s entreaty and offered Máirtín a post as lecturer in the Irish department of the university. Ó Cadhain gratefully accepted the offer and began his university career at Trinity College on 2 February 1956. He proved to be an industrious and highly successful lecturer who prepared his notes and plans with great diligence. He also initiated a series of night classes open to the general public which were exceptionally well-received and are talked of even to the present day by many enthusiastic ex-students. Máirtín was made Head of the Irish department as Associate Professor in 1967, Professor in 1969, and Fellow in 1970, the year of his death. He is said to have had an informal manner with his students and sought to get to know each of them personally. He arranged to have them go to Conamara every summer to stay with choice Irish-speaking households.

Ó Cadhain was dogged by ill-health: blood pressure, headaches and insomnia, which often saw him preparing his university material in the middle of the night. And, of course, he was deeply affected by the untimely death of his wife in 1965. His own death in October 1970 was equally untimely.

Ó Cadhain’s literary work

Máirtín Ó Cadhain was brought up in an environment rich in folklore and storytelling. A voracious reader and keen listener, he wasted no time on sport or cards in his student days. He began publishing material in 1928, during his first year teaching in Camus.

During the first ten years of his literary career, he published mainly folklore material — proverbs, songs and stories he had collected and recorded in Conamara.

In 1929 he had his first short story published, and in 1930 his first literary review appeared in the the monthly western newspaper, An Stoc. He was to continue writing short stories and literary reviews for the rest of his life, as well as three novels.

His first foray into translation, which he undertook while still teaching in Camus, was published in 1932, Saile Ní Chaomhánaigh (Sally Kavanagh, Charles Joseph Kickham), under the translation scheme introduced by An Gúm (the Irish-language publication unit in the Department of Education). The same publisher included his translation of a short story, ‘A Short Suit’, by Lynn Doyle in Rogha na gConnachtach (1937).

Although not a singer, he recognized the value of the musical heritage of his native Conamara and collected a considerable number of songs heard at home. He worked on his first collection during 1937–8 while in Dublin, although this collection was unfortunately lost as he rapidly moved lodgings, being on the run at the time due to his political activities.

While at a loose end due to lack of steady employment in Dublin during this period, he embarked on writing a series of short stories, most of which appeared in his first collection, Idir Shúgradh agus Dáiríre agus scéalta eile, published by An Gúm in 1939.

In 1940 he began recording lists of words and phrases for a dictionary project in preparation by An Gúm. These words and phrases had not appeared in Dinneen’s Irish-English dictionary (1927) and, indeed, some of them he had only heard from the mouth of his own mother, which motivated him to record and preserve them. This work was interrupted while he was interned in the Curragh 1940–44 but he resumed his labour of love on his release, spending many periods at home at his source in Conamara.

While in the Curragh, he translated some popular songs from English, The Shawl of Galway Grey and Bonnie Mary of Argyle and also a few socialist songs, L’Internationalé and The Red Flag. During his period working as a government translator, Ó Cadhain had translations published of short stories from Breton, Welsh and French. During this period his magnum opus, and his only novel published during his lifetime, Cré na Cille, appeared, at first in the form of weekly extracts in the national newspaper, Scéala Éireann (The Irish Press), from February to September 1949, and then in book form, published by Sáirséal agus Dill (1949). Máirtín had submitted the manuscript to the annual national Irish-language literary competition run by Oireachtas na Gaeilge in 1947 and won first prize. This shows that he had been working on it during the years before taking up the post of government translator. His second and third collections of short stories also appeared during this period, An Braon Broghach published by An Gúm in 1948, and Cois Caoláire published by Sáirséal agus Dill in 1953. His further three collections were published by Sáirséal agus Dill in 1967, 1970 and (posthumously) in 1977. He wrote two further novels which he felt were not ready to be published. However, having taken advice from trusted academics, Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain decided to have them published. One of them, Athnuachan, which won first prize in the annual Oireachtas literary competition in 1951, was published by Coiscéim in 1995 with a substantial Foreword by the eminent critic, Monsignor Brendan Devlin. His third novel, Barbed Wire, written in the early 1960s, edited by Professor Cathal Ó Háinle, was published by Coiscéim in 2002. Máirtín was exceptionally proud of this work and said during the course of his famous lecture in 1969, Páipéir Bhána agus Páipéir Bhreaca, that he thought it was his best bit of writing ever.

Ó Cadhain joined the government translation service at an extremely controversial time for the written form of the language when a new standard spelling and grammar were being developed and introduced. The spelling standard was published in 1947 and the grammar standard in 1953. Máirtín was appointed to a committee of three to tease out some problematic issues but, while enthusiastic for the work at first, he found himself at odds with one of his colleagues, his boss in fact, and fell foul of the committee. He had mixed feelings about the standards, apparently, as he saw the value of a consistent written form of the language although preferring his own usage.

It was during this same period that Ó Cadhain was recruited to write a weekly column for the national newspaper, The Irish Times, from 1953–6. His columns covered a variety of topics: his reflections as he travelled abroad, the condition of Scottish Gaelic and the economy and politics of Scotland, Irish politics – especially concerning the North, literature, drama, censorship, urban life in Irish-language novels, Freud’s and Jung’s opinions on literature, the Gaelic mind vs Europeanism, the meaning of ‘Irish literature’, the Irish language and its revival, the Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking areas), words and their meanings, placenames, and educational matters.

Since the time when he was a young teacher in Camus and Carnmore, Máirtín Ó Cadhain was often heard addressing crowds with spirited rallying orations in support of improved conditions for Gaeltacht communities. Many of these were published, e.g. ‘Claidhe na Muice Duibhe ar Mhuintir na Gaeltachta’ (The Black Pig’s Dyke around the Gaeltacht community) in the weekly Irish-language newspaper An tÉireannach (September, 1934). After moving to Dublin, he continued to deliver rousing and sometimes controversial lectures on aspects of Irish-language literature, as well as on aspects of Irish politics and history, many of which were published or summarised in the media or in literary journals. Others, chiefly concerning politics and the Irish language, written mainly in the 1960s were published as booklets or pamphlets. The most famous of these is probably Páipéir Bhána agus Páipéir Bhreaca (Blank Pages and Pages Written-on), published by An Clóchomhar in 1969, the text of a significant and revealing lecture he gave at the Merriman Winter School on 31 January 1969. The lecture was somewhat autobiographical and included the author’s reflections on the state and possible fate of Irish-language literature.

Ó Cadhain and politics

Máirtín Ó Cadhain was a passionate and dedicated advocate of the Gaeltacht and its people. He cared deeply about fairness for the people and for the language, and could not countenance what he considered to be hypocrisy. For example, there is an account in his biography, De Ghlaschloich an Oileáin: beatha agus saothar Mháirtín Uí Chadhain (27–8), of how he and two other primary teachers refused a 10% increase in salary when the government decided in 1930 to award that amount to primary teachers teaching in the Gaeltacht. The three asked that the money be given instead to the Gaeltacht population. Their request was ignored, however, and they were paid the increase. Furthermore, he was dead set against Fianna Fáil because, in his view, they were rife with treachery from the outset – he believed that de Valera had abandoned the Republic around 1925. (For more on this topic, see Mac Aonghusa, 88 et seq.)

During his early years teaching in Camus, Máirtín became a member of the Irish Volunteers. His housemate there, Seosamh Mac Mathúna, had been involved with the Volunteers since 1918 and was by this time an adjutant in the Conamara Battalion. Máirtín, who had been interested in republicanism since his student days, persuaded Seosamh to swear him in with an oath of allegience, and it was not long until he was made a captain in the area. He accompanied Mac Mathúna to every meeting and they travelled throughout Conamara on Volunteer business. When he moved to Carnmore in February 1932, Máirtín continued to be a Volunteer captain in that area.

During those years he honed his skills as an organisational operator, information-gatherer and strategist. He founded a branch of Conradh na Gaeilge (The Gaelic League) in Carnmore, and was appointed to the Conradh na Gaeilge business committee for Connaught in 1935.

Along with his old friend, Seosamh Mac Mathúna, and Críostóir Mac Aonghusa (a local teacher, activist and county councillor), Máirtín founded Cumann na Gaedhealtachta (The Gaeltacht Association) in 1932 to achieve rights and equity for Gaeltacht people. A motion was passed to seek to have some of the lands being recovered by the government from landlords set aside and given to Gaeltacht people. On 7 July 1934 another organisation called Muinntir na Gaedhealtachta (the Gaeltacht people) was formed, with Máirtín as secretary, to speed up the campaign to secure lands in County Meath for poor Gaeltacht families.

While the government emphasised saving the language, Máirtín and the other activists put the emphasis on saving the Gaeltacht community. After many protests, including cycling campaigns to County Meath and Dublin in order to persuade the government to give some good land to Gaeltacht people, the government finally gave in and, as a result, the Ráth Chairn Gaeltacht was established in 1935, although it did not get official Gaeltacht status until 1967.

On 19 August 1934, Ó Cadhain gave a famous speech while opening a festival in An Cheathrú Rua in Conamara, which was published in the monthly Irish-medium newspaper, An tÉireannach (September, 1934) under the title ‘Claidhe na Muice Duibhe ar Mhuintir na Gaeltachta’ (The Black Pig’s Dyke around the Gaeltacht community).

In April 1936, Muinntir na Gaedhealtachta organised a large parade through the streets of Galway in honour of those who lost their lives fighting for Irish freedom. In the graveyard, the rosary was said in Irish by Máirtín Ó Cadhain. Alan Titley quotes the following excerpt from The Connacht Tribune, 18 April 1936:

Fianna Fáil and the IRA united on Sunday in paying a tribute to the memory of those who lost their lives during the fight for Irish freedom. After a parade through the city streets an oration was delivered at the New Cemetry, Bohermore, by Domhnall Ó Donnchadha, Dublin… The following bodies took part in the parade in addition to the Labour band and two pipers:- Fianna Fáil, Muinntear na Gaedhealtachta, Cumann na mBan, Old IRA, Fianna Éireann, Cumann na gCailíní and relatives of the dead. At the graveyard the rosary was recited in Irish by Máirtín Ó Cadhain.

His name was to be mentioned again in The Connacht Tribune two months later. In June 1936, the government banned a ceremony to commemorate Wolfe Tone (one of Máirtín’s greatest heroes) at Bodenstown, County Kildare, and he was to head up the crowd set to travel from Galway to the ceremony. Alan Titley provides the following report from The Connacht Tribune, 27 June 1936:

There was considerable Garda activity in Galway on Saturday night and Sunday morning as a result of the government ban on the Republican parade at Bodenstown, County Kildare. About twenty-four men were rounded up in the city during the early hours of Sunday morning and were detained at Eglington St. Garda station until 2.30 pm on Sunday afternoon… Galway Garda authorities refused to give any information about the people arrested, but a number of those who had been placed under arrest supplied their names and particulars to a Connacht Sentinel representative after their release on Sunday afternoon.

In the interview they stated that amongst those arrested were the brothers Mc Namara, and Mr. Martin White, three men who had traveled from the Lisdoonvarna area to join the Galway party going to Bodenstown; Messrs. Edward Walsh, Patrick Walsh and Fursey Walsh, three sons of the late Mr. Michael Walsh who was killed by the Black an Tans during the Anglo-Irish war; James Fay, Joseph Coyne, M. Coyne, Patrick Smith, J. Burgoyne, F. Rabbite, J. Whelan, T. Mc Donagh, J. Collins. J. Carter, J. Folan. One County Mayo man, Séamas de Búrca, was also arrested in Galway.

(Connacht Sentinel)

As a result of this episode, the local bishop ordered the school manager to dismiss Ó Cadhain from his teaching post in Carnmore. Although Máirtín appealed to the bishop, it was to no avail. The bishop had had a letter read from the altar saying that it was wrong to take part in the activities of the Volunteers. A similar thing had happened the previous year in Waterford for the same reason. Teachers had no security of tenure in those days, which shows the extent of totalitarian power then held by the Church in educational affairs. Although he was chairman of the West-Connaught branch of the INTO, the primary teachers’ union refused to stand by Máirtín.

Nonetheless, Máirtín did not desist from his republican activities. He took part in the Galway by-election campaign to elect Count George Noble Plunkett and was one of his nominators: ‘Proposed by Mrs. Agnes Walsh, High St., Galway, seconded by Mr. Mtn. Coyne, Carnmore West, Galway (The Connacht Tribune, 8 August 1936)’.

After moving to Dublin at the end of that year, Máirtín acted as a recruitment officer for the Volunteers during 1937–8 and was apparently very successful in the role as he is said to have enrolled many young men into becoming members. He was appointed to the Army Council in April 1938, and was soon its Secretary. Although on the run in 1939, he was arrested in September in the Conradh na Gaeilge office at 14 Parnell Square and interned in Arbour Hill prison until December of that year. He went on the run again in 1940 as the secret service was keeping a close eye on him.

In April 1940, a friend of Máirtín’s, Tony Darcy, died on hunger strike in Mountjoy prison in an effort to attain political status for republican prisoners. Máirtín gave the oration at the funeral in Headford, County Galway, where he was arrested after the funeral and interned in the Curragh Camp, County Kildare for over four years. Both his parents died during this period of internment; he was allowed home on special leave for the first of these funerals but not for the second. Meantime, his friend Tomás Bairéad was actively attempting to have him freed, and finally succeeded on 26 July 1944. From then until the 1960s, he seems to have scaled back his political activism and concentrated on working, writing, translating and, of course, reading.

In 1963, Ó Cadhain was a founder member and leader of a pressure group called Misneach (courage), founded as a response to the government’s perceived failure and hypocrisy in regard to the revival of Irish. According to research carried out by Hugh Rowland, one of its members, Seán Ó Laighin, claimed that Misneach wanted to break out of the old trench of Irish organisations and inspire revolution and fundamental reform in society in order to focus on the decline of the Gaeltacht and the disinterest of political and religious leaders in regard to the issue. In an interview with Rowland, another member, Mícheál Mac Aonghusa, said that Misneach wanted to act in a very informal and unstructured way to ensure that agitation could be instigated unhindered. Their main aim was to reclaim the country from the establishment, and to return the ownership of Ireland and her property to the people of Ireland so that the people could live as truly Irish people with those values and attributes native to them (For more on this topic, see Ó Cadhain, Gluaiseacht na Gaeilge: Gluaiseacht ar Strae, 1970). The concept of reclamation was a comprehensive one in which culture, socialism, republicanism and the economy would be united for the common good

, explained another member of Misneach, Séamas Ó Tuathail, who also said that the government were acting sanctimoniously with regard to the Irish language in that their rhetorical statements were falling foul of their practical actions

while at the same time the ‘offficial’ Irish-language movement (which Ó Cadhain called organisations such as Conradh na Gaeilge, Gael Linn and Comhdháil Náisiúnta na Gaeilge) was too involved with the political establishment of the State

:

…the official movement, as Máirtín [Ó Cadhain] called them, were too quiet and were following the Government down the road and hoping that positive things would happen when in fact negative things were happening… one example I remember in particular was the closing of the preparatory colleges…

(These excerpts from Rowland have been translated by Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain.)

Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s philosophy was very attractive to young people who wanted a more active and radical approach. Máiréad Uí Dhomhnaill told Rowland that she was influenced by Ó Cadhain, whom members of Misneach likened to Che Guevara, because he was a strong and powerful person and leader who had a very strong presence and who succeeded very well in rousing the members to fight (Interview with Rowland 2013).

Two years after the founding of Misneach another very different organisation was founded – the Language Freedom Movement (LFM), which had the following aims written into its constitution:

The objects of the organisation shall be to promote a realistic approach towards the Gaelic language and to remove compulsion, discrimination and other objectionable practices from the State language policy.

The LFM wanted an end to the compulsory condition that a student needed to pass the Irish examination in the Leaving Certificate for the certificate to be awarded. They also demanded that having fluency in Irish as a compulsory factor in applications for jobs in the public service be abolished. As Rowland points out, the aims of the LFM and those of Fine Gael in regard to the status of Irish were much the same at this time.

As might be expected, these two organisations were soon at loggerheads and, in the words of Rowland: Members of Misneach identified the LFM as their adversary and the conflict suited them as a means to achieve their own aims

. He then describes an LFM meeting held in Jury’s Hotel in Dame Street in June 1966 when Ó Cadhain and other members of Misneach and the IRA were waiting in hiding in the room next door. Once the meeting began they rushed in and turned the room and its contents to chaos, upturning the speakers’ tables and chairs and shouting during the speeches. As the meeting was being closed, they started singing God Save the Queen.

Rowland goes on to explain that these new tactics employed by Misneach were rooted in civil disobedience and were influenced by Saunders Lewis, a Welsh political and language activist who had links with both the political party Plaid Cymru and the Welsh Society. Lewis had given a lecture on BBC radio in 1962 titled Tynged yr Iaith (The Fate of the Language) in which he recommended revolutionary methods for promoting Welsh. Ó Cadhain translated Lewis’s lecture to Irish and it was published in booklet form as Bás nó Beatha (Life or Death) by Sáirséal agus Dill in 1963. In so doing, Máirtín aimed to let Irish-language organisations in Ireland know about the Welsh methods of activism, protest and demonstration, and the result of this was the founding of Misneach.

Another example of their activity was the placing of a picket on a Fianna Fáil rally held in O’Connell Street in Dublin before the general election in April 1965. A white paper on the revival of Irish, ‘An Páipéar Bán um Athbheochan na Gaeilge’, had been published in January of that year and Misneach took this opportunity to publicly vent their aggravation with Fianna Fáil. Seán Lemass, or the ‘Taoiseach gan Ghaeilge’ (Taoiseach without Irish) as he was labelled by Misneach, was standing on a platform and members of Misneach were throwing copies of the white paper at him and shouting tarraing siar an Páipéar Bán

(withdraw the White Paper). This was a method of protest used to shame the government and is an example of Ó Cadhain’s dramatic propaganda which was entirely different from the the respectability of the official movement.

In the words of Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh:

In Ó Cadhain’s case, even when he agreed with their aims, as he often did, he seldom thought their methods were suitable or effective. They were not sufficiently urgent. They didn’t understand the urgency or the enemy properly; they could not or did not bother to carry out the bold or ugly deeds that were necessary to achieve their aims (‘Máirtín Ó Cadhain, An Stair agus an Pholaitíocht: Athmhachnamh’.

(In: Léachtaí Cholm Cille XXXVII: 166–207).

Misneach organised a fast in Dublin and Belfast in 1966 during the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising to highlight the government’s neglect in respect of the Irish language and the Gaeltacht.

An important element of Misneach’s influence was that it inspired other Irish-language and Gaeltacht groups during the 1960s to take a stand. For instance, Gael Linn protested at the absence of Irish-language programmes in prime-time slots on Teilifís Éireann (Irish Television), and at the apparent lack of government commitment to implementing the proposals outlined in the Report of the Commission on the Irish language, and Gluaiseacht Chearta Sibhialta na Gaeltachta (Gaeltacht Civil Rights Movement), of which Ó Cadhain was a founding member in 1969. Their aims included the establishment of a local planning and development authority for the Gaeltacht regions, a comprehensive education plan, and a Gaeltacht radio station. Thanks to their efforts, Raidió na Gaeltachta (Gaeltacht Radio) was established in 1972. The movement made important demands and succeeded in most of them, and it can be fairly said that the movement’s work has left a visible footprint on Gaeltacht life, especially in Conamara, to the present day.

As to other campaigns in which Ó Cadhain was involved, Proinsias Mac Aonghusa wrote the following in 1976: ‘Until Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s biography is written, and written excellently, there will not be comprehensive information about all his campaigns and how he planned them’. However, Mac Aonghusa continued by mentioning some of them:

…the long campaign against Christopher Morris, the LFM man; the one against John D. Sheridan, the well-known Catholic, about the authority of priests in national schools; the solo campaign which forced Mc Court’s Teilifís Éireann to provide contract forms in Irish; various arguments with Proinsias Mac an Bheatha, one of his bêtes noirs; his campaign to have the facts of the story about the murder of Barney Casey in the internment camp on the Curragh revealed to the public; his own military campaign in England in 1939, and his work in the Volunteers and for the Volunteers from the first day he joined the Republican Army until the day he died.

(Mac Aonghusa, 89; translated by Iontaobhas Uí Chadhain).

Ó Cadhain’s legacy

Máirtín Ó Cadhain left an indelible mark on the tapestry of the Irish language and its prose literature. We have seen, from the breadth and variety of his works and activities, how he contributed to the lives of Gaeltacht people such as those living in Ráth Cairn, to Irish lexicography through his compilation of word and phrase lists, to academic studies of Irish-language literature through his published articles on folklore and his many literary reviews, to Irish-language politics through his many talks, lectures, interviews, booklets and pamphlets. And above all else, he contributed to Irish-language literature a corpus of outstanding creative work, his three novels and six collections of short stories (some of which are anything but short).

While his work was viewed as difficult by many, citing his penchant for piling rare words and phrases one after the other, and was increasingly passed over by academia, a situation exacerbated by the fact that his work was allowed to go out of print for decades, there is no genuine excuse for this neglect. Nor for the fact that his publisher refused permission repeatedly to have his magnum opus, Cré na Cille, translated into English although permission was given for Norwegian and Danish translations (published in 1995 and 2000 respectively). When a new publisher took over the rights in 2009, Ó Cadhain’s works began to be reprinted. Not only that, but English translations of some of his short stories began to appear. Finally, two translations of Cré na Cille were commissioned, the first The Dirty Dust, translated by Alan Titley, published in 2015, followed by the second in 2016, Graveyard Clay, translated by Liam Mac Con Iomaire and Tim Robinson, both published by Cló Iar-Chonnacht and Yale University Press. These English translations have spawned translations into a number of other languages including German, Czech, Hungarian, Italian, Turkish. A translation into Nederlands (Dutch) by Alex Hijmans made directly from the original Irish appeared in 2017. Further translations to other languages are said to be in development.

Cré na Cille has also been dramatized, firstly for radio (by RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta in 1973), then for the stage (adapted by Macdara Ó Fátharta and performed in 1996 and 2006), and finally a film version with English subtitles (written by Macdara Ó Fatharta, and directed by Robert Quinn) was released in 2007.

Some of Ó Cadhain’s short stories have also been dramatized (and in some cases televised), including An Taoille Tuile (RTÉ 1983, adapted by Tony Hickey, and directed by Dónall Farmer), An Bhliain 1912 (2002, a contemporary dance show entitled Aistir – Voyages adapted by a Swiss dance company, Tanz Ensemble Cathy Sharpe, and performed in several venues around Ireland, exploring the theme of migration and drawing parallels between the Irish and Swiss experience), Glantachán Earraigh (adapted for stage by Proinsíos Ó Duigneáin, Splódar, Manorhamilton, County Leitrim), An tOthar (adapted and directed by Maidhc P. Ó Conaola, Aisteoirí an Spidéil), Fios (adapted and directed by Maidhc P. Ó Conaola, Aisteoirí an Spidéil), An Eochair (2006, adapted as a three-act play and directed by Fidelma Ní Ghallchobhair, Aisteoirí Bulfin), and Círéib (2011, a one-act play adapted by Fidelma Ní Ghallchobhair, and co-directed with Gearóid Ó Mordha, Aisteoirí Bulfin).

Aisteoirí na Tíre recorded a reading of an excerpt from an unpublished Ó Cadhain play, Typhus, broadcast by RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta during his centenary year in 2006, and Scoil Éigse Chamais performed a dramatized extract from the same play in 2017. Also in 2006, RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta broadcast a performance of An Fear Bacach sna Flaithis, adapted by Joe Steve Ó Neachtain from a draft found among Ó Cadhain’s papers and directed by Máirtín Jaimsie Ó Flaithbheartaigh. It was performed on stage the same year as a ‘story drama’ by Cumann Drámaíochta Ráth Chairn.

Much critical work has been written about aspects of Ó Cadhain’s corpus and it is likely that much more will be written. We have begun to collect such material and will make it available here with the authors’ permission.

English language material

The ‘legacy’ section of our website is a collection of writings and multimedia recordings (in both Irish and English) which either engage with the discourse on Ó Cadhain’s linguistic, cultural and political legacy or which derive in some way from from that legacy. We are expanding this collection gradually. Material in English currently includes the following.

Máirtín Ó Cadhain 1906–1970

By Tomás de Bháldraithe.

This article gives an overview of Ó Cadhain’s life and work. It was originally published in 1974, in Lochlann 6.

The Nation or the ‘local organic community’?: Ó Cadhain versus Ó Droighneáin

By Fionntán de Brún.

An analysis of a clash of ideologies regarding the Standardisation of the Irish language.

Máirtín Ó Cadhain (Aitheasc Luan na Tríonóide 2002)

By Cathal Ó Háinle.

An exploration of Ó Cadhain’s life and work.

Máirtín Ó Cadhain — No Ordinary Man

By Declan Kiberd.

A retrospective of Ó Cadhain’s life and work, originally published in Irish Examiner in 2006; the centenial year of his birth. Kiberd was a student of Ó Cadhain’s whilst at Trinity College Dublin from 1969 to 1970.

Máirtín Ó Cadhain — The Man on the Stamp

By Mae Leonard.

A memory of Ó Cadhain, originally broadcast on RTÉ Radio 1 as part of Sunday Miscellany in 2008.

Máirtín Ó Cadhain

By John Montague.

A poem in memory of Ó Cadhain.

Samuel Beckett and Máirtín Ó Cadhain: The Vehemence of the Dead

By Professor Robert Welch.

Given at the centenary commemorative event in Saint Partick’s College, Drumcondra, on 12th October 2006.

audio recording available here 🔊

In this talk, Professor Welch, in his search for commonalities between Irish writing in the literatures of both languages since the time of the cultural revival, honed in on similarities between the works of Ó Cadhain and Beckett, both born in the same year. For a culture to be operational, he argued, such commonalities must exist. He found Tomas Kinsella’s concept of ‘the divided mind’ disturbing, and sought to identify commonalities in the purposes of Irish-language and English-language literature in Ireland.

He thought that these two authors were confronting the death-throes of two different cultures: Ó Cadhain in the case of Irish-language and Gaeltacht culture, and Beckett regarding western culture.

Both explored anguish, and the quality of anguish: Ó Cadhain contemplating the agony of physical work, especially among women, and Beckett also understood the agony of physical pain from his personal experience. Examples from the works of both authors are given which illustrate their understanding of physical pain.

Beckett addresses the certainties and uncertainties of life, and of the ego — recognizing that all the world inhabits the surd or the irrational.

In Cré na Cille, Caitríona Pháidín’s hatred for her sister Neil is fixed and immutable. Professor Welch spoke of the deep intimacy of hatred and observed that Irish people are particularly good at hatred. He thought that the intensity of the hatred releases the ferocity and vehemence of the speech.

Beckett has this same fixity on gloom — the only possible response is speech.

Another theme visited by both authors is the relationship with the mother, the feminine.